16 minutes

Symbolic Execution and Angr

Symbolic Execution is mainly focused on converting a program made up of a concrete set of instructions into an equation-like format. This is achieved with two core components:

Symbols

Different values in a program(such as the user input) are substituted with Symbols(variables or placeholders). These symbols pertain to a domain full of values, allowing us to explore the program in a much more open form, basically “walking through the program” with a domain full of values(handled by any one of the constraint solving backends like Z3) instead of walking a fixed path due to a fixed hard-coded value/input.

Execution Paths

The phrase “walking through the program” essentially means carrying out the set of instructions in the program. These set of instructions define a particular path, which when executed, brings the execution flow of the program to a particular state, unique to that path. An execution path, therefore, represents a possible execution of the program that begins somewhere and ends somewhere else.

Checkout the slides for a practical viewpoint over symbolic execution.

From a practical view point, the ability to reason (solve) large boolean functions makes symbolic execution possible. Programs and instructions are converted into formulae, and then these formulae are reasoned with to see if a particular path of execution is possible. However, testing all the paths of a binary can be cumbersome since the number of paths grow exponentially. Therefore, we solve problems that have a certain structure to them instead of completely random stuff such as random bitvectors or integers. We imply such techniques on something that one is confident about, so symbolic execution coming out to be undecidable or an ETA of time as large as the age of universe(literally) is pretty infrequent, although it does happen.

Moreover, exponential path growth kept aside, one must consider the fact that each of these paths have exponentially growing inputs, which would take even longer. Therefore, the fact that we are fuzzing with a focus on paths rather than the user input itself makes sure we are better off.

Another thing to consider is that a strategy often used at a branch is to take both branches, collect their respective events and merge in the end to make sure everything works fine. But that doesn’t work well with modern, huge programs. So we usually prefer to do “one path at a time exploration”. that is, take a path, create a formula for it and find an input for it with a particular aim in mind such as satisfying some constraint, violating a property or causing a crash with an out of bounds err. If this path doesn’t achieve the aim, we try out a different path.

The strategy of approach is chosen between “path by path” reasoning, “all paths at same time” reasoning or a set of heuristics to make a search traceable(pruning paths early in control flow graphs depending on their end result) would not necessarily make a huge difference to the outcome, but can make a huge difference to the efficiency of resources. Thus, an intelligible decision should be made to prevent path explosion. Some sort of random testing is done to explore initial set of paths, and the we can start looking at the paths in the neighborhood.

Angr

I would highly recommend reading through the Angr docs for a comprehensive surface-level understanding of different classes and methods supported by Angr, with their usecases, as well as reading Federico Lagrasta’s intorductory series on Angr.

Now, I’d be amiss if I didn’t highlight the fact that while Angr manages to be a stroke of brilliance, it isn’t that tough. It’s the lack of resources that proves to be overwhelming, especially with so many version changes. There are a lot of writeups you could read through, but that doesn’t help much from an absolute beginner’s point of view. Therefore, I intend to solve the CMU bomb binaries in order to learn Angr, and will be documenting the journey in the hopes that it would probably be useful to someone, someday.

View the PPT for a quick intro to Symbolic Execution.

x64 CMU Bomb Lab

There are a bunch of different phases(read: levels) that we’ll have to solve.

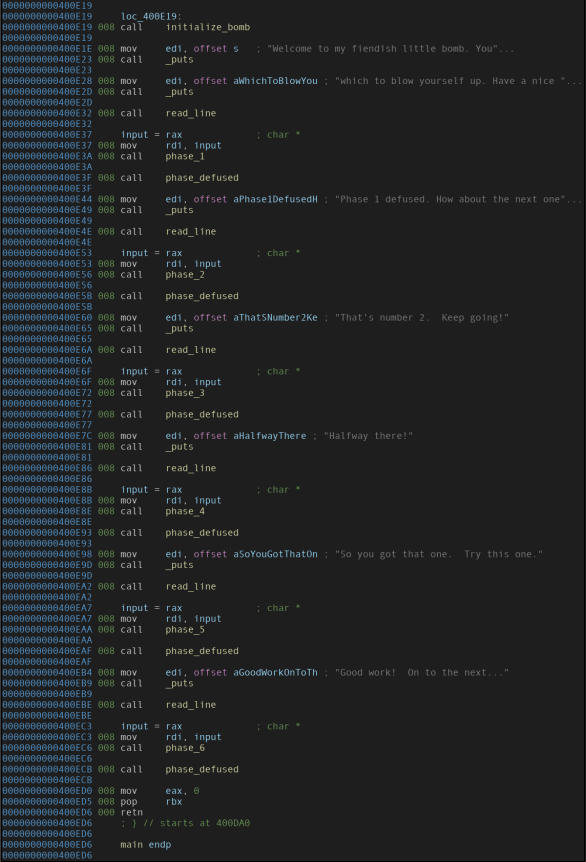

The binary looks as follows:

Disassembly of the important part of the “main” function (a handy reference for addresses).

Disassembly of the important part of the “main” function (a handy reference for addresses).

It tells us:

- The binary just calls a bunch of different functions sequentially, and we gotta pass through them all to be able to successfully defuse the bomb.

- A value is returned from the function

read_line. Going by the calling convention of x86_64, a function returns a value using theRAXregister. Thus theinputvariable gets the value returned from the function. - Going by the calling convention of x86_64, a function’s first argument is passed via the

RDIregister. Thus, the value returned from theread_linefunction is passed onto the next phase function every time.

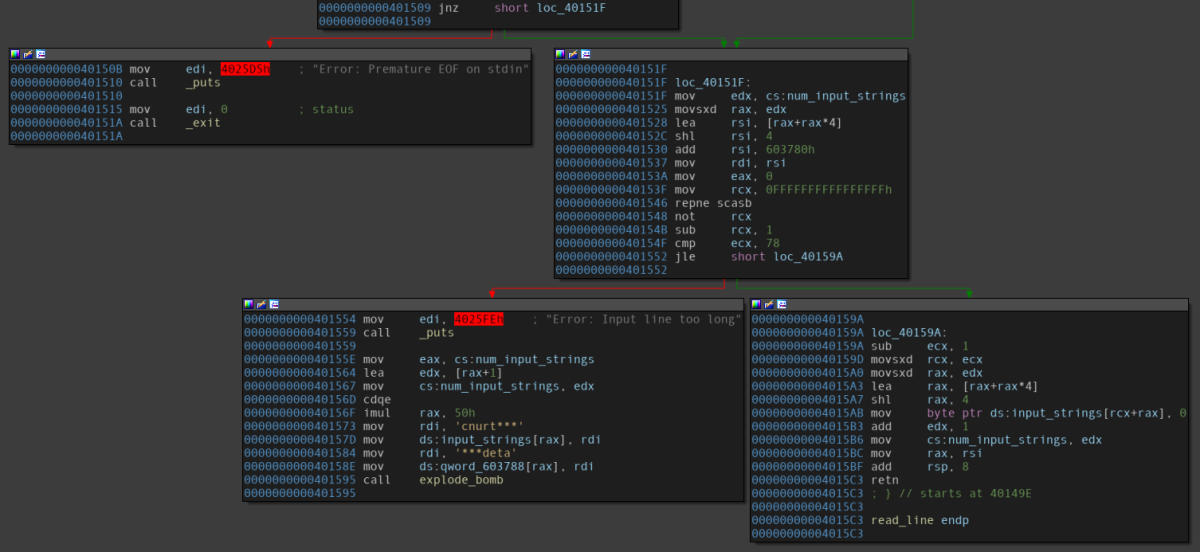

Disassembly of the “read_line” function.

Disassembly of the “read_line” function.

Taking a look at the read_line function’s ending code blocks, it can be seen that a particular comparison with 78 (decimal value) gives rise to branches - one with an error (saying that the input is too long), while the other one returns. It can be easily deduced that the user input seems to be limited to 78 characters, and it is the value which is returned.

We’ll take two approaches for each phase:

Approach 1: Blind Walk

We’ll let Angr do what it does best: walk all over the binary without any care in the world. We treat the function as a black box and do not look into it’s working. We just let Angr do it’s work. This does take a lot of time, as a result of which, I didn’t use it after the first phase.

Approach 2: Targeted Walk

This approach is a more targeted approach based on our knowledge of the inside workings of the function. The main focus here is to find out how the user input and the values to be compared are provided to the function, and then applying a tailored method to exact this comparison value.

Phase 1

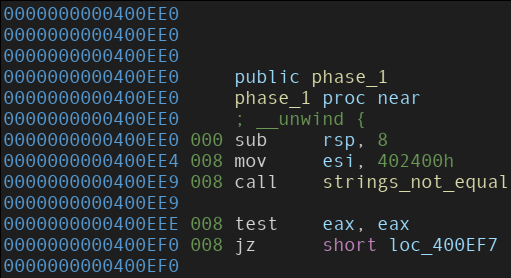

Function: phase_1

Disassembly of the “phase_1” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_1” function.

From the disassembly, we can see that following the calling convention goes, an address is being moved into the ESI register.

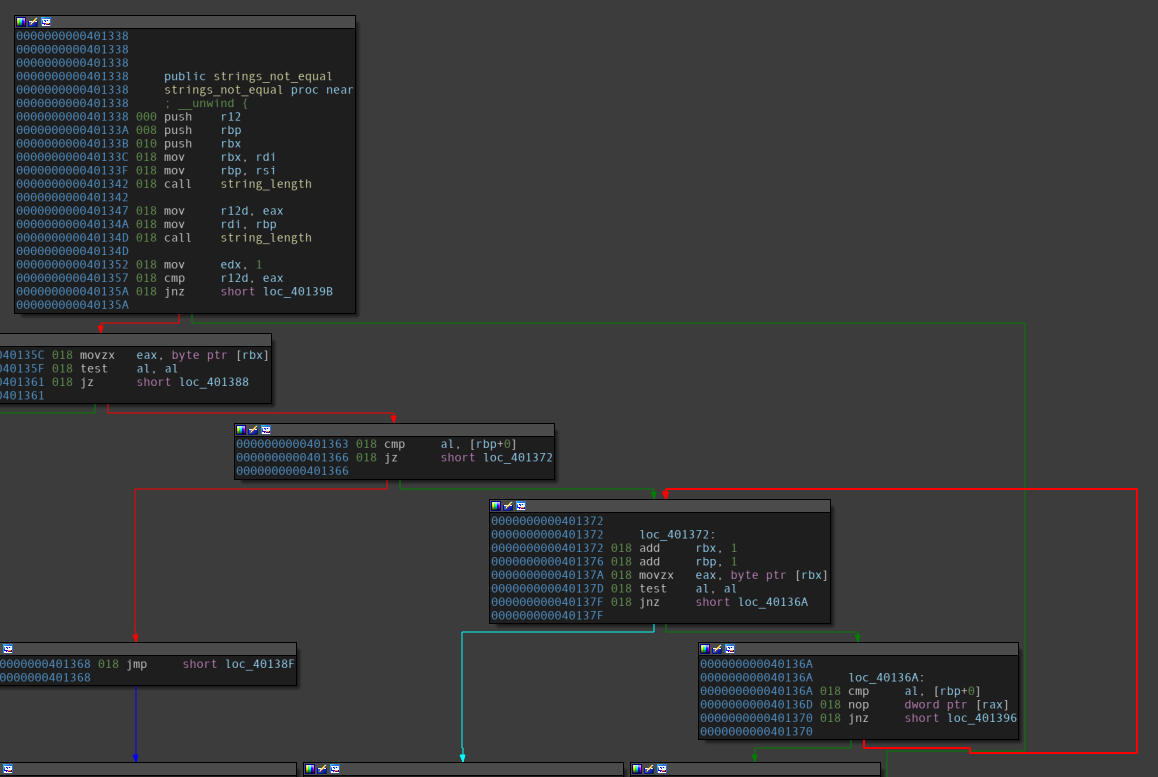

Disassembly of the “strings_not_equal” function.

Disassembly of the “strings_not_equal” function.

A few observations follow:

- The values stored in both, the

RSIand theRDIregisters are moved toRBXandRBPin the top left block. - A loop construct is present in the bottom right blocks where value from

RBXis moved toEAXbyte-by-byte and thenRBPandALare compared.- This can be deduced as a string comparison.

Thus, it can be conclusively said that the address, which was moved into the ESI register earlier, is the address of the string to which the user input is compared.

Therefore,

- User input:

RDIregister - Comparison value: string’s address in

ESIregister

Thus, we can strategically hook this function and see if we can exact this string from the memory.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approaches taken to solve this phase.

Phase 2

Function: phase_2

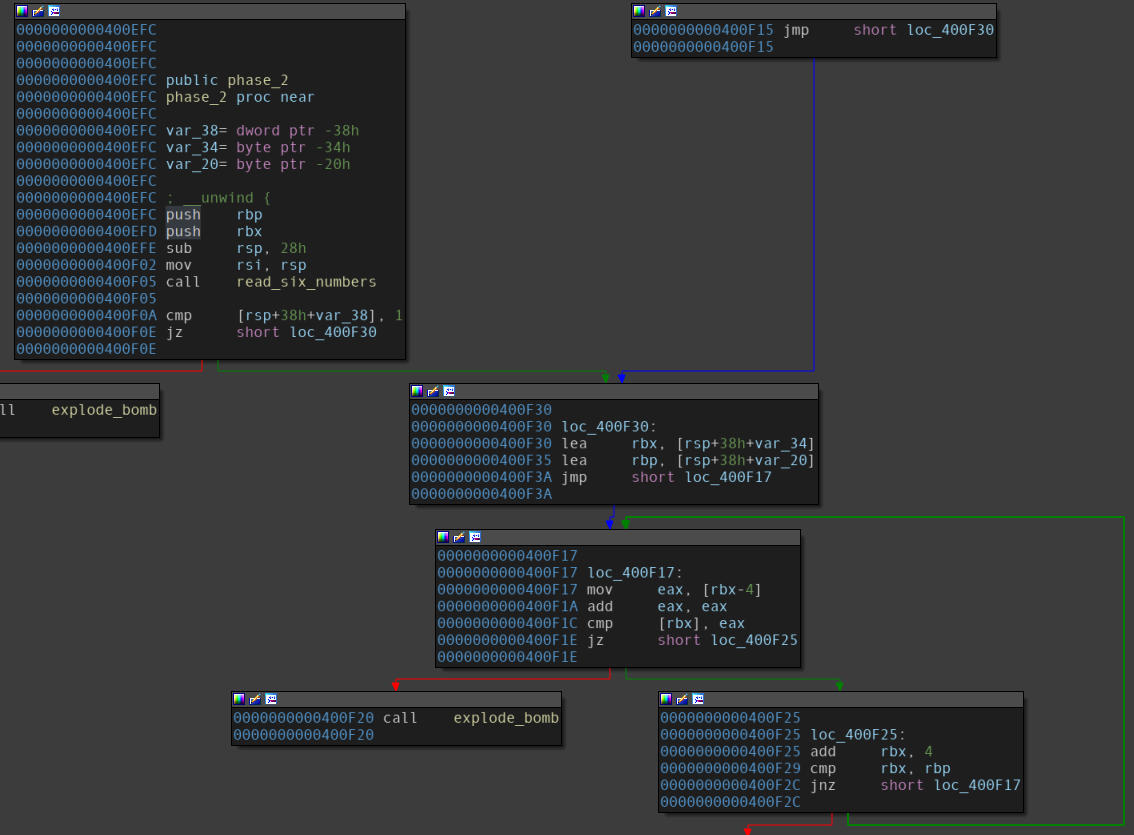

Disassembly of the “phase_2” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_2” function.

A few observations follow:

- A function, namely

read_six_numbers, is called in the first block.- The compare instruction on the end of the first block makes sure the first integer in the user input should be 1.

- A loop construct is present in the bottom right blocks.

- Values from different indices of the array represented by

RBXare being compared among themselves. - Since

RBXgets the address of an array referenced with theRSPregister in the previous block, the number array seems to be on the stack.

- Values from different indices of the array represented by

Although Angr works out well despite us explicitly asking it to take care of it, it might become necessary for us to explicitly take care of it. All we need to do is add a constraint on the symbolic value should such a case arise. This is done by simply adding the constraint on that symbolic value via the state solver.

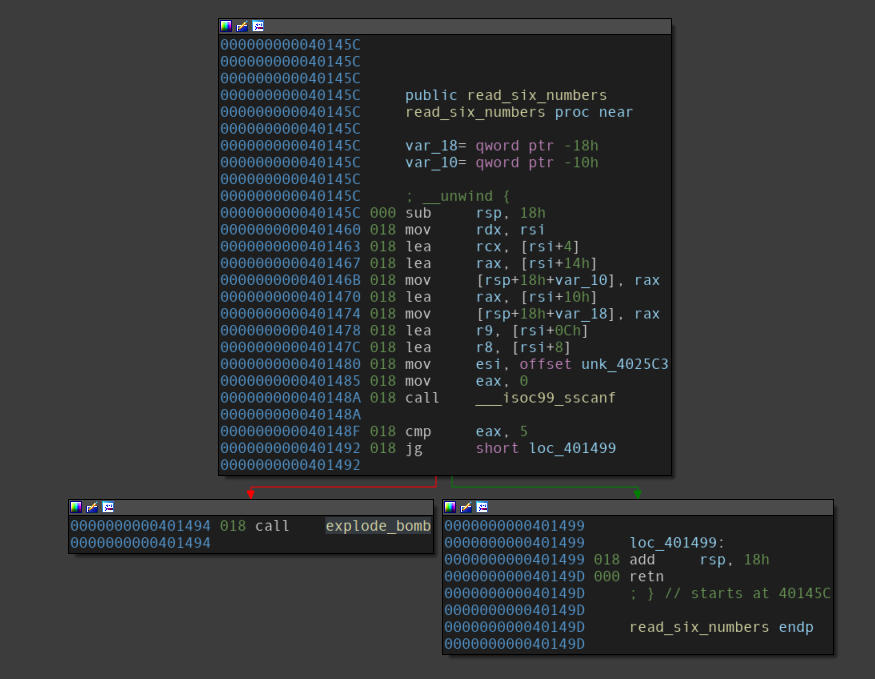

Disassembly of the read_six_numbers function.

Disassembly of the read_six_numbers function.

Simply maps the string passed as an argument to the function via RDI (user input) to a format string passed via ESI to sscanf.

Basically reads six numbers from the user input, since after return, EAX would contain number of successful inputs scanned(return value of sscanf) and it is supposed to be greater than 5, referring to the end of the first block.

Since sscanf is being used and inputs are being mapped in memory, it confirms our suspicion that the number array remains on the stack.

Let’s check the stack using a debugger to verify.

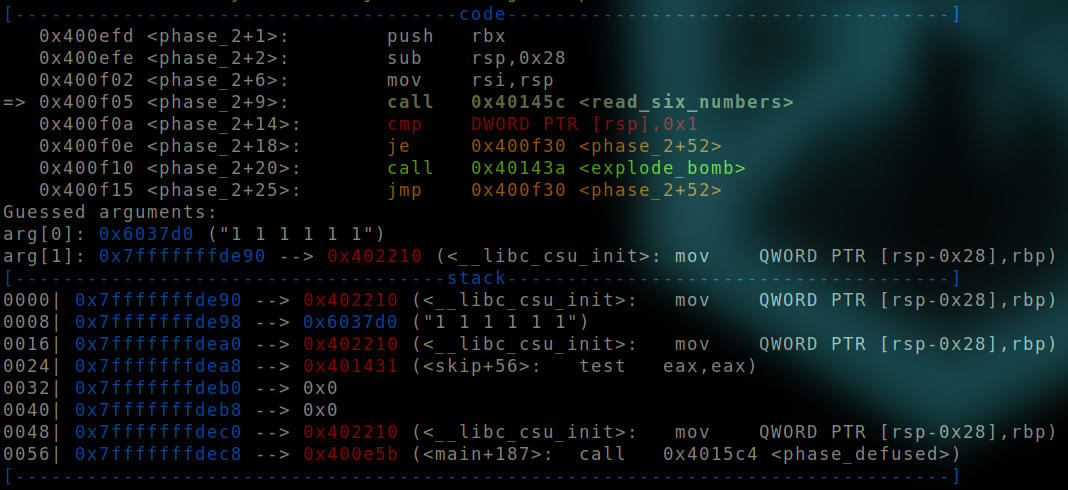

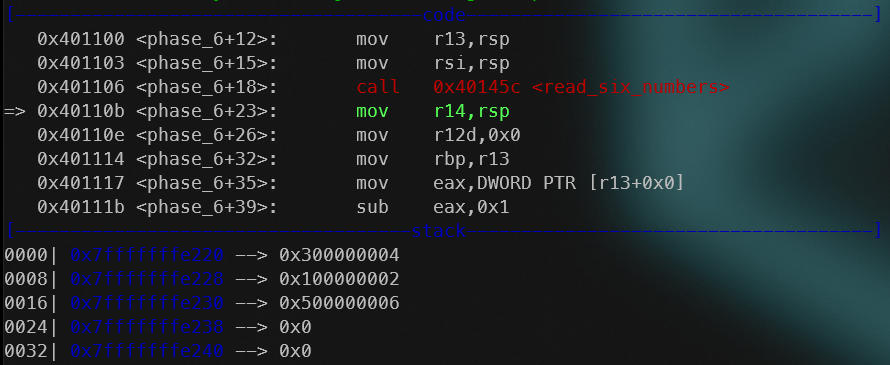

Before read_six_numbers is called.

Before read_six_numbers is called.

We can see that an argument of 1 1 1 1 1 1 is provided to the function.

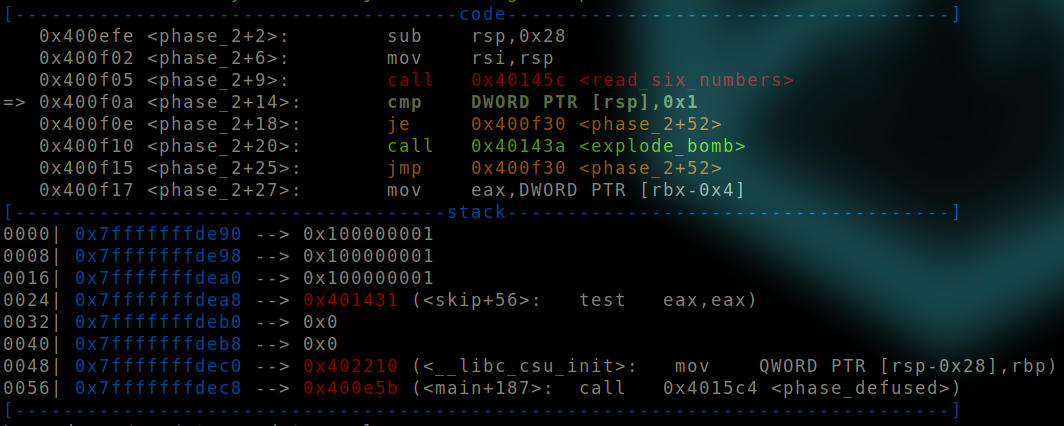

After read_six_numbers is called.

After read_six_numbers is called.

We can see that the input we gave is immediately pushed on the stack by the function call. Note the seemingly weird format of the number. We would need to keep this in mind while deciphering the values when we dump them.

Therefore,

- User input:

RDIregister ⇨ pushed on stack. - Comparison value: number array itself.

Since no value is pushed before these numbers in phase_2, we don’t need to setup the stack and we can start symbolic execution right here and push the input on the stack. Since nothing else is pushed onto the stack all the while, it can be popped off the stack at the end.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approaches taken to solve this phase.

Phase 3

Function: phase_3

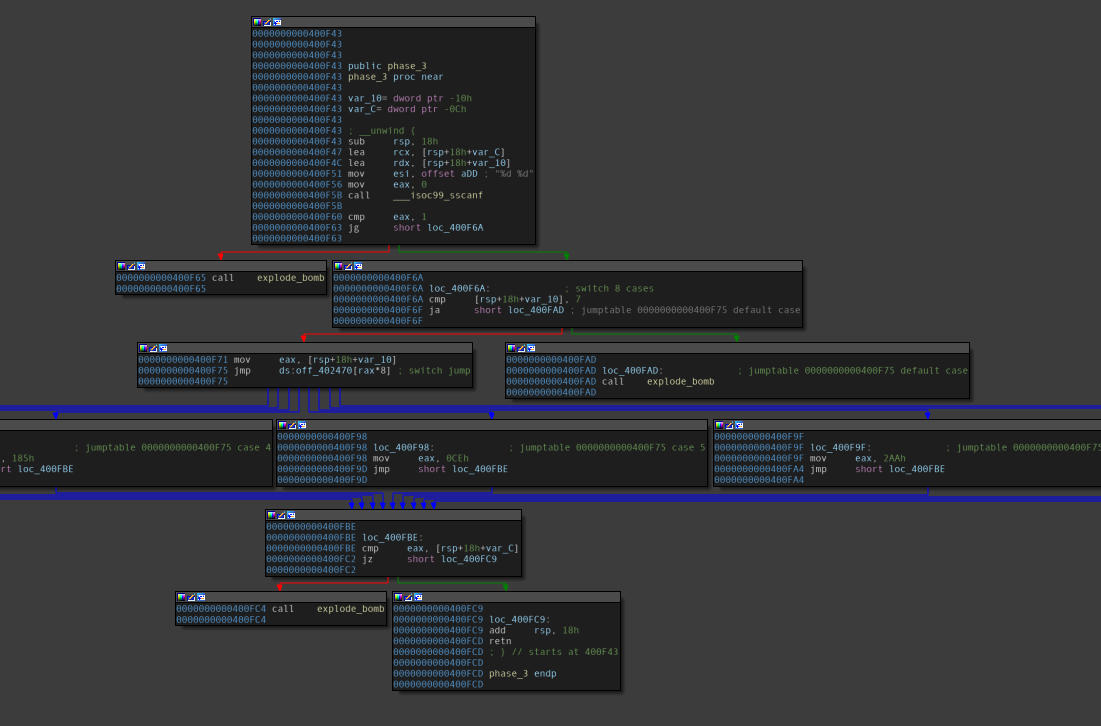

Disassembly of the “phase_3” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_3” function.

A few observations follow:

- This function has a jump table(essentially a switch case that has been resolved by the compiler).

- There are 8 cases present.

- The function simply maps the string passed as an argument to the function via

RDI(user input) to a format string passed viaESItosscanf. - The first block shows the format string resolved. It clearly shows that a set of two integers are given as input.

- Going through the assembly, it becomes clear that it’s a pair-set value, that is, the second value will be accepted based on what the first value is.

So we once again verify the stack structure and see if our previous approach would work.

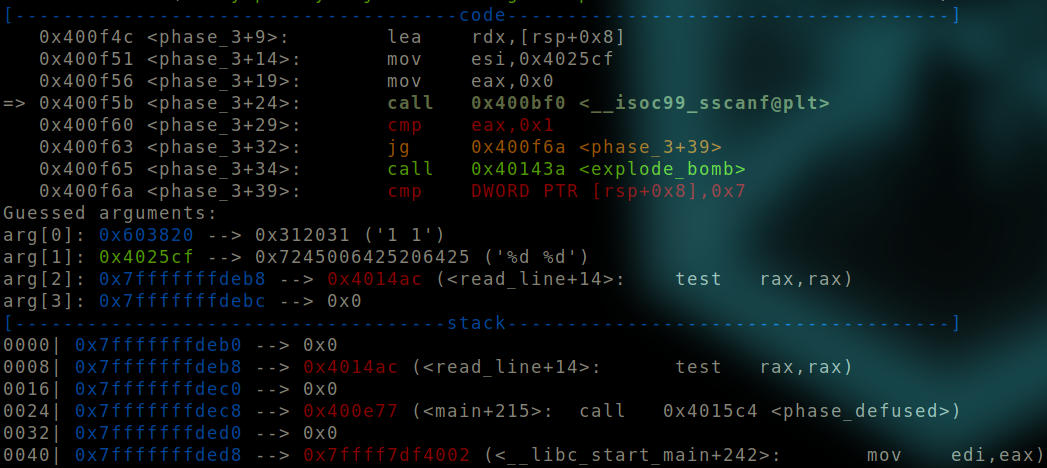

Before “sscanf” function is called.

Before “sscanf” function is called.

We can see that an argument of 1 1 is provided to the function.

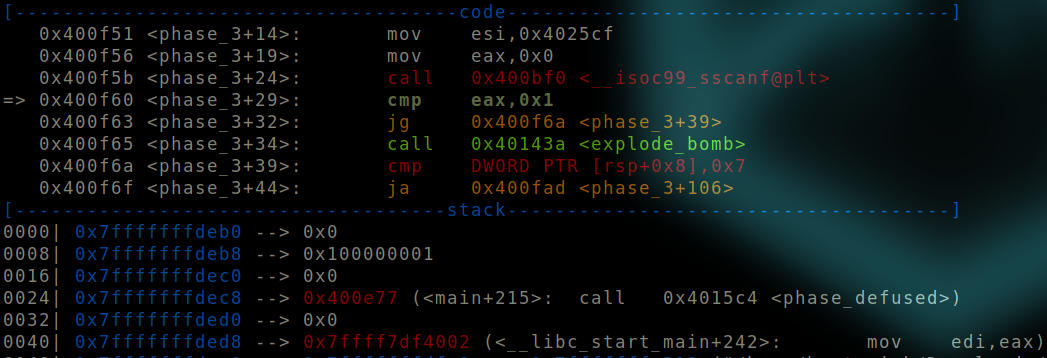

After “sscanf” function is called.

After “sscanf” function is called.

The top of the stack is a null value while our input is right below it. Therefore, a kind of a stack setup is required before we can proceed.

Therefore,

- User input:

RDIregister - Comparison value: a switch case with one to one comparison between the two integers entered.

Since no other push to stack exists in the function, we can pop values like before, while keeping in mind to pop the value we setup the stack with first.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approaches taken to solve this phase.

Phase 4

Function: phase_4

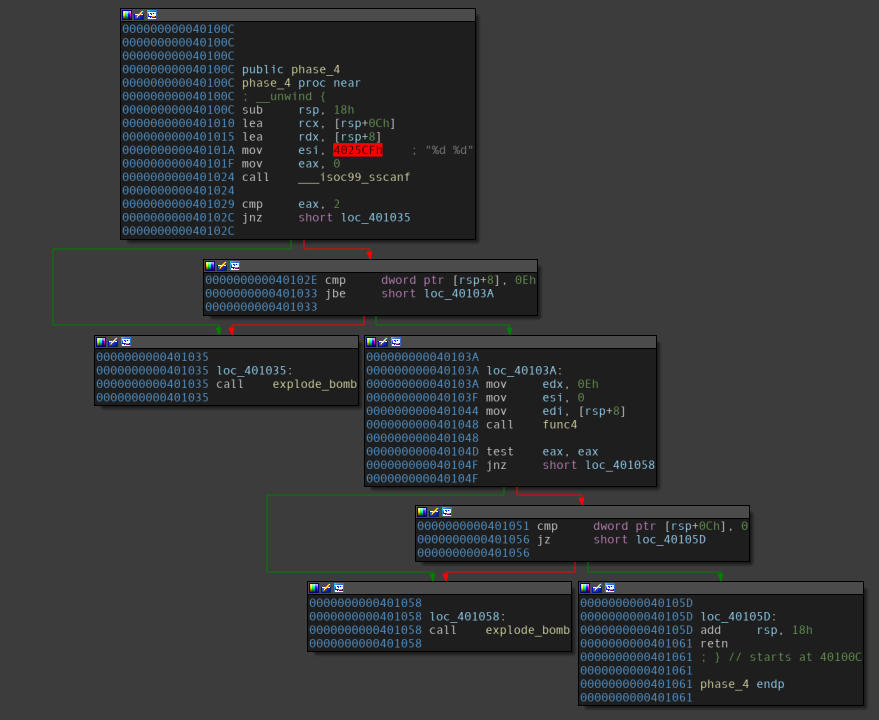

Disassembly of the “phase_4” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_4” function.

A few observations follow:

- The function takes up an input with two integers, and passes them onto another function, namely

func4. The result of this function is based on the result of this sub-function, and therefore needs to be paid special attention to. - Before this function is called, three values are moved into specific registers, and the registers chosen make it clear that these are the arguments to this function. Thus, it received the arguments:

(<user_input>, 0, 14). - Right after the code block where this function was executed, we can see our other argument being comapred against

0x0. Since our main focus would be on this function, we can explicitly put the second input as0x0when we put in the flag, and not bother about it at the moment.

All we need is that function to return a 0x0.

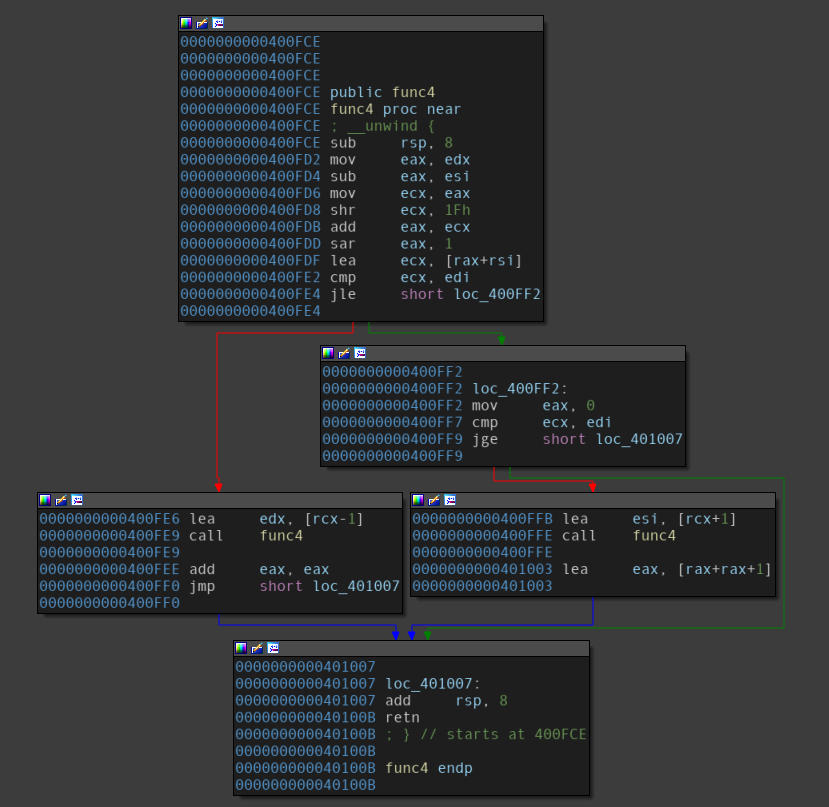

Disassembly of the “func4” function.

Disassembly of the “func4” function.

From the first look, this function comes out to be recursive in nature. Now, that might not have been that big of a problem if we had not been using a tool to solve the intricacies presented by this problem. You see, a recursive function might cause an automated tool(working with no concrete values, only symbolic ones) to get stuck in it’s own loop, causing a path explosion.

Since checks are in place to prevent the tool from going down a rabbit hole, therefore instead of tinkering with the recursion depths here, let’s just focus a little bit deeper onto the function. We can see that going along with the single middle block will do the trick.

Therefore,

- User input: Moved into the

EDXregister. - Comparison value: Operations carried out on the input with the values

0x0and0xE.

So what we have to do is:

- Setup the registers as they are supposed to for the function call.

- Go through the first block so as to reach the single middle block.

- Satisfy the comparison at the end of the single middle block.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approaches taken to solve this phase.

Phase 5

Function: phase_5

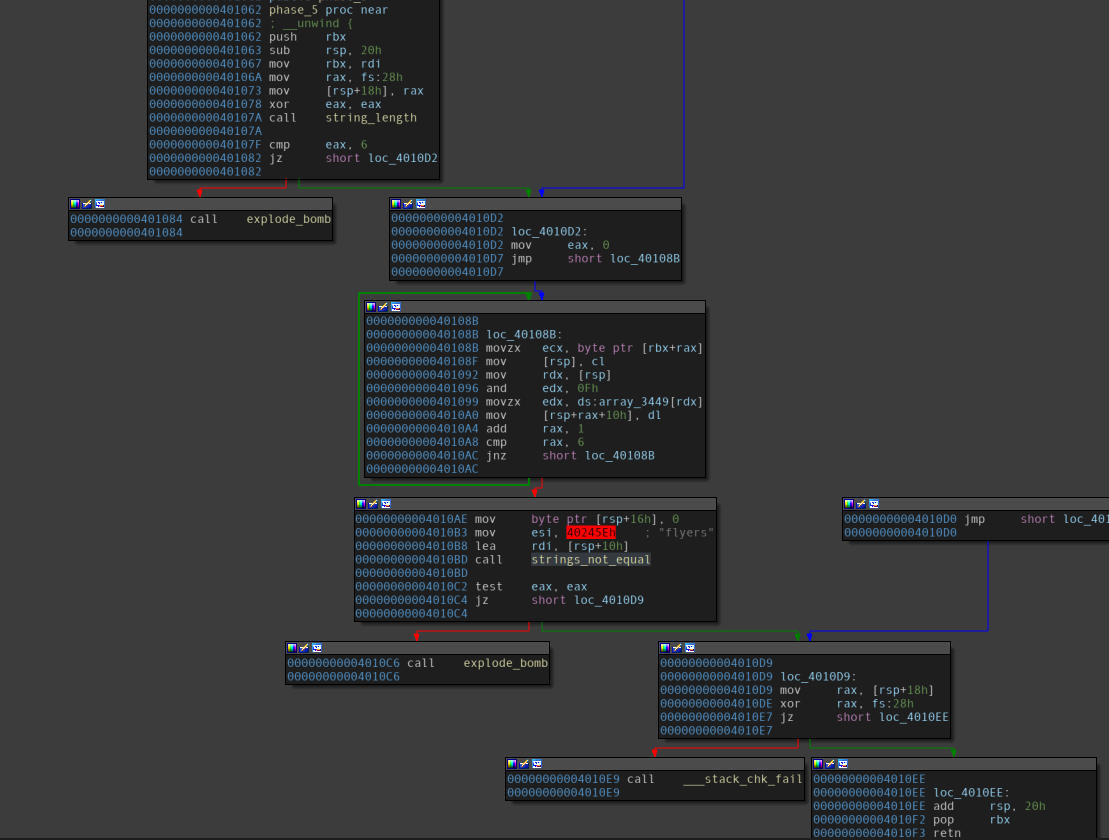

Disassembly of the “phase_5” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_5” function.

A few observations follow:

- The function takes up a string as an input.

- Input length is restricted at

0x6, with reference to the compare instruction at the end of first block. - A loop can be observed in the middle.

- Performs some computations on every character of the string.

- The

andoperation in the middle of the loop may require us to undo a mask.

- The computed string is compared with the string

flyers.

Seems pretty straightforward.

But what about the input? A string input needs to be placed somewhere in the memory. Since there seem to be no push operations, we need to find the address where the input is being stored at. We’ll look it up in a debugger.

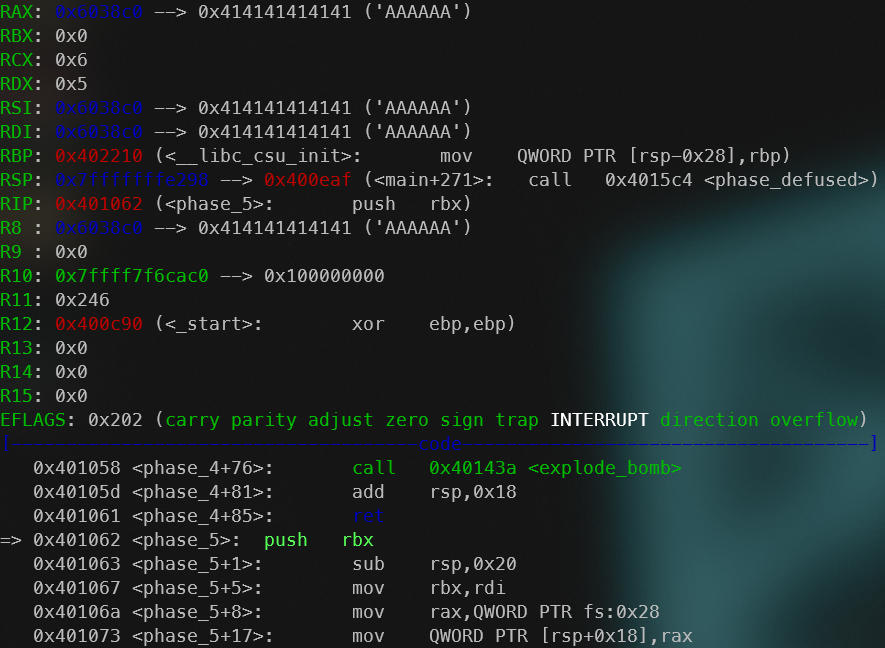

Beginning of “phase_5” function.

Beginning of “phase_5” function.

Therefore,

- User input: Stored at the address

0x6038c0. - Comparison value: Compared with string

flyers(evident following the cross references in the disassembly) after a bunch of manipulations to the input.

So what we have to do is:

- Setup the registers as they are supposed to for the function call.

- Go through the first block so as to reach the single middle block.

- Satisfy the comparison at the end of the single middle block.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approaches taken to solve this phase.

Phase 6

Function: phase_6

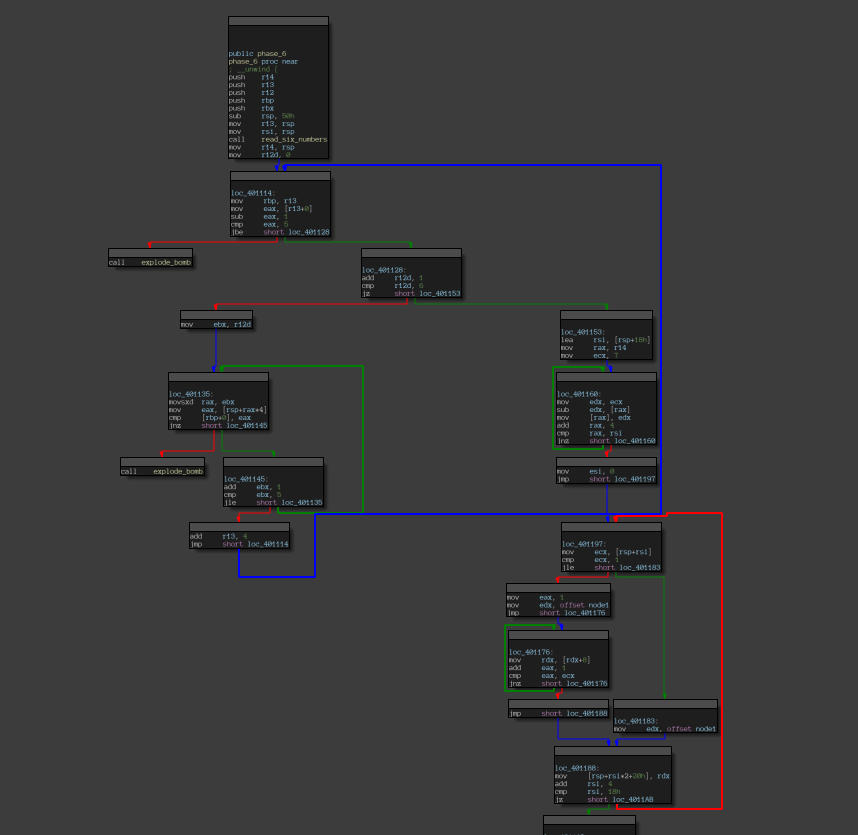

Disassembly of the “phase_6” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_6” function.

From a perspective where we just worry about setting up the input, this function essentially seems no different than phase_2.

There seem to be two sets of loops, prominent blue and red arrows indicating their flow. One modifies the input (the one with the blue arrow) and the other one verifies it (the one with the red arrow).

A function, namely read_six_numbers, is called in the first block, which maps our input onto the stack.

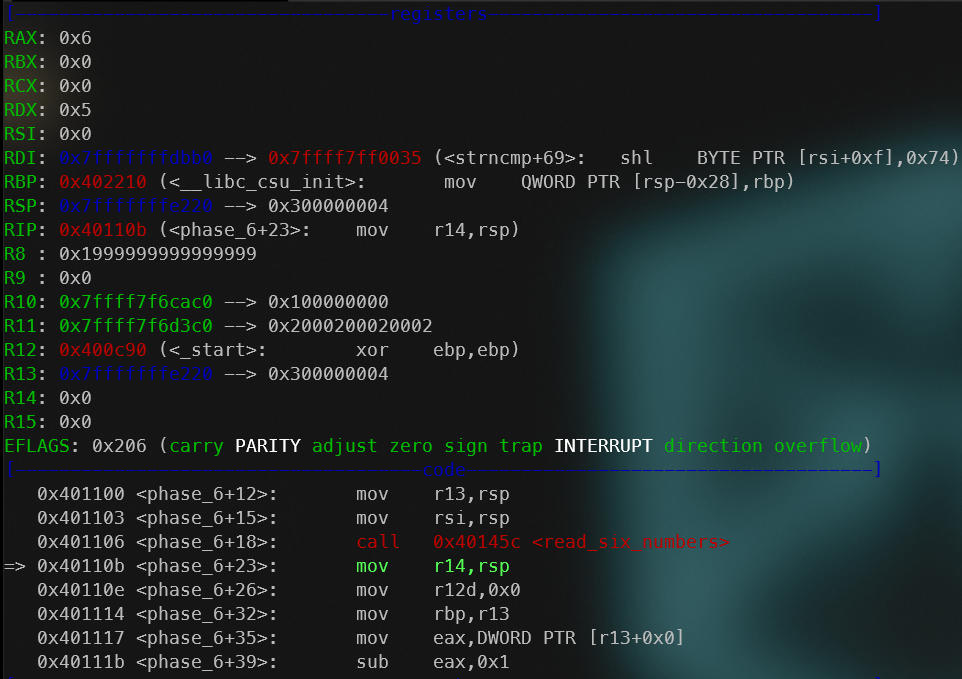

Stack after the “read_six_numbers” function is called.

Stack after the “read_six_numbers” function is called.

An added point of interest is the state of registers. R13 gets the stack address (where the input we provided is at the top) and then is iterated through all the values on top of the stack (our input) in the block right after the first, where it is essentially made sure that each number is less than or equal to 6. This could be added as a constraint (not a necessity though).

Registers after the “read_six_numbers” function is called.

Registers after the “read_six_numbers” function is called.

We could simply apply the same approach as we did in phase_2 (by pushing values to stack and popping in the end, minding the formatting), with a slight change: reversing the manipulation did by the first loop denoted by the blue arrow in the picture showing the disassembly of the phase_6 function.

This is because the instructions perform some form of manipulation (observed by the fact that the Angr gave an answer that wasn’t right on popping, although it fit the conditions, verified by running in a debugger), that rearrange our input using their addresses. It’s more than believable since a further look at the disassembly showed a linked list being initialized with the values given as input, and it becomes the subject of the manipulations in the loops shown by the red arrow in the picture showing the disassembly of the phase_6 function.

Since we got the modified input (from the “not so wrong” output), we could simply reverse that transformation to get the original input.

The instruction to be focused on is 000000000040115B mov ecx, 7

Therefore, we could just subtract the values we get from Angr to get the original input to bypass the stage.

Alternative Approach

Instead of pushing the values onto the stack, we’ll find out the address where the values are put and store them right there, just to see if we can make it work.

We’ll start from the beginning of the function, and add a hook to the read_six_numbers function so as to make it return without doing anything, while we explicitly store the symbolic values in the memory.

To find out the address where we need to put the values, let’s open the binary in the debugger.

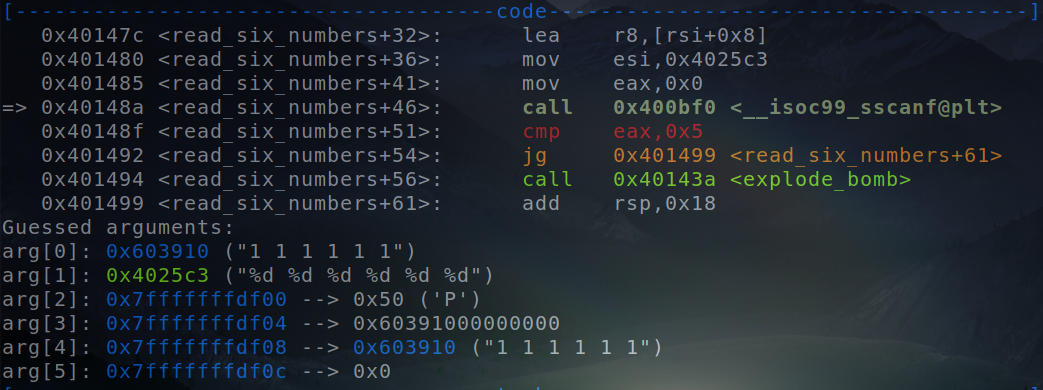

Arguments to the “sscanf” function.

Arguments to the “sscanf” function.

We can clearly see the addresses to which the values are to be stored. Thus, we save the values right on these addresses to form a sequence, as expected by the binary.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approaches taken to solve this phase.

Secret Phase

Function: secret_phase

Discovering the Secret Phase

Let’s start bu discovering the secret_phase function.

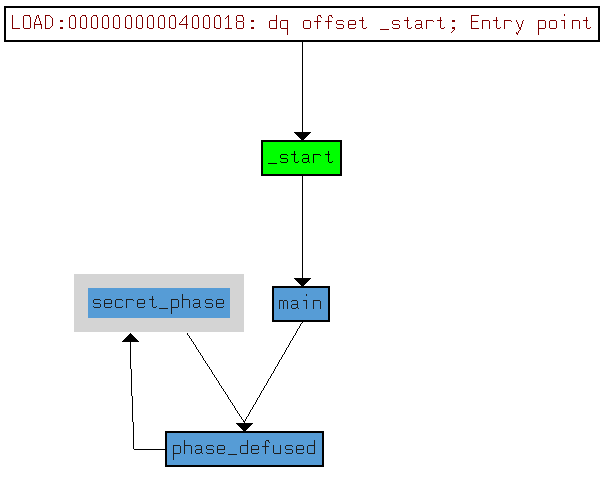

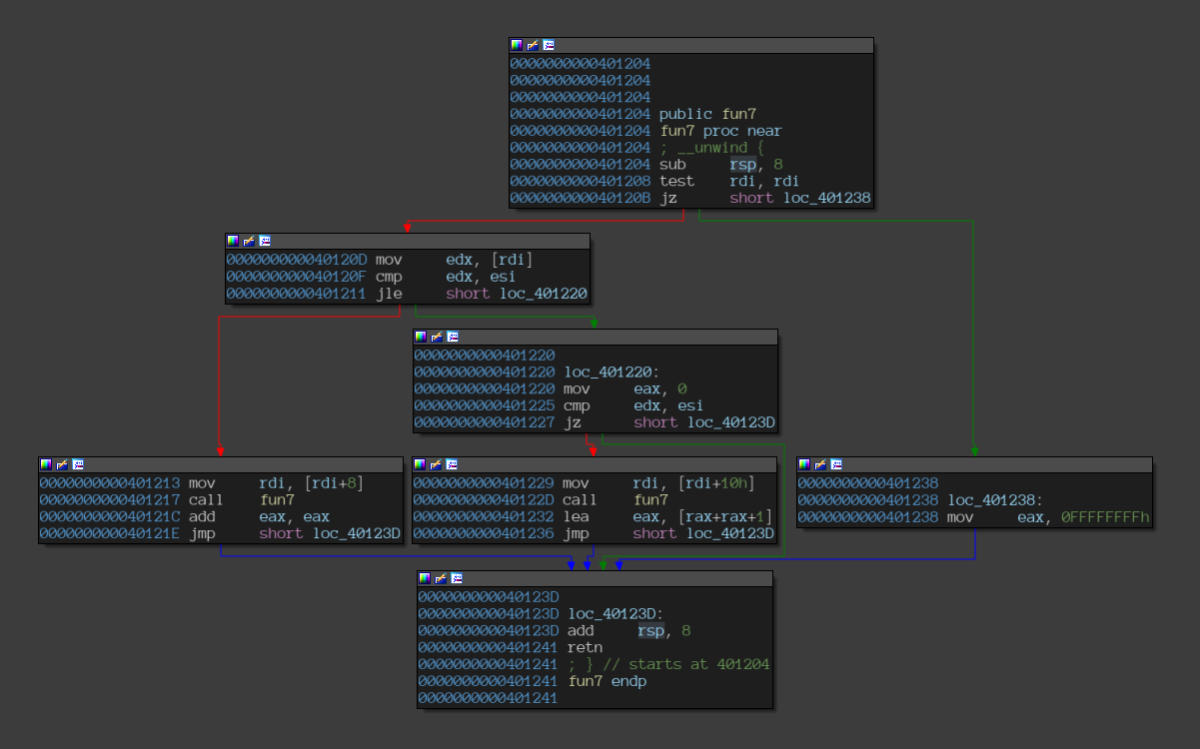

Cross references chart.

Cross references chart.

From the _xrefs char_t, we can see that only one function invokes the secret_phase function.

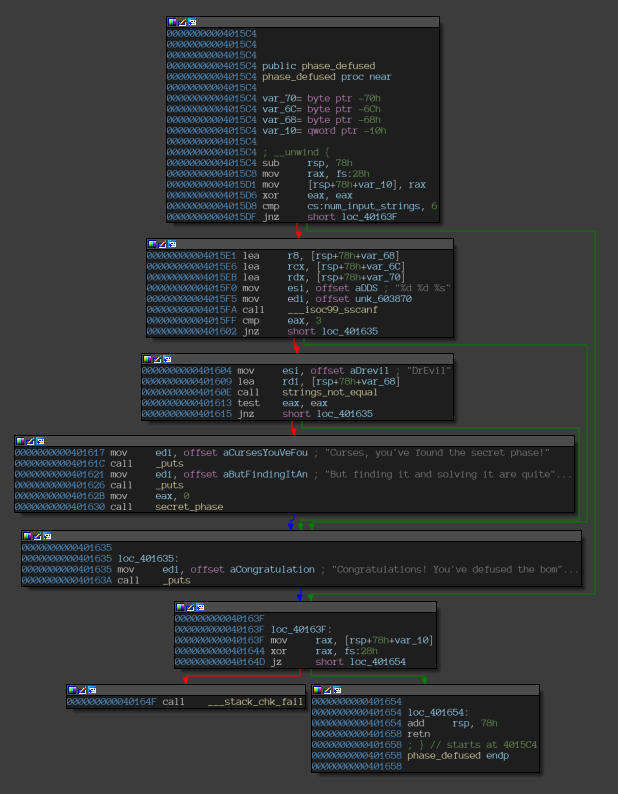

Disassembly of the “phase_defused” function.

Disassembly of the “phase_defused” function.

The phase_defused function simply checks a couple of conditions based on which, it invokes the secret phase.

The middle blocks are responsible to check if our input are worthy of unlocking this secret phase. It takes on the input from one of the phases and verifies it to decide whether to unlock the secret phase. The point of interest here is that the address being used here(0x603870), in the call to sscanf to source values for the variables, is hard-coded and is not of the buffer that stores the address. A search for cross references to it yield nothing. So to find out that phase, we use the debugger and monitor any changes made to this address (using hardware watchpoints).

Hardware watchpoint triggered.

Hardware watchpoint triggered.

The hardware watchpoint is triggered right when the input is given for the phase_4 function. Therefore, the input for this phase needs to be modified so as to unlock the secret phase.

Now we know how to unlock it, we’ll just pass a symbolic value to Angr hoping that it’ll be able to give us the string input which will be the key.

Call to “sscanf” function.

Call to “sscanf” function.

We can just slide in the symbolic value at the address where the string will be dereferenced(0x7fffffffdf10) and then let Angr do it’s magic over the bunch of instructions that carry out the comparison.

After we get the key to the phase, we can move on to solving it.

Solving the Secret Phase

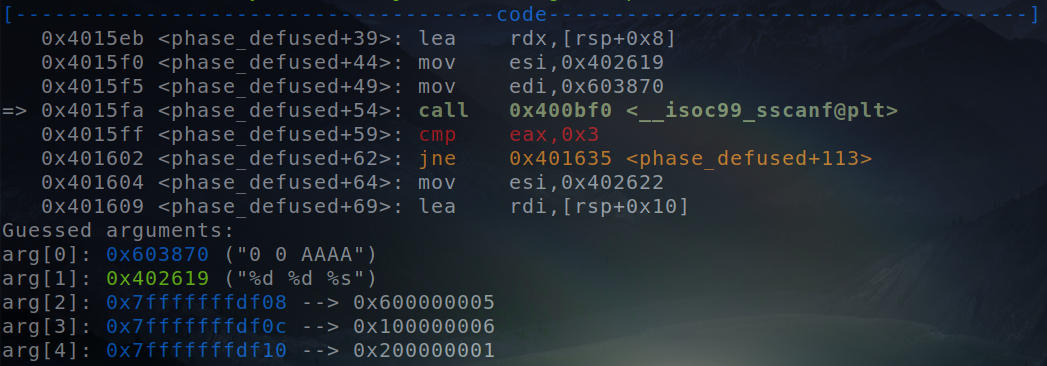

Disassembly of the “secret_phase” function.

Disassembly of the “secret_phase” function.

A few observations follow:

- The function takes the string input and converts it into a long.

- Only a single function, namely

fun7, needs to be bypassed to solve the phase.

It’s pretty simple and straightforward, especially compared to what we have done in all the previous phases.

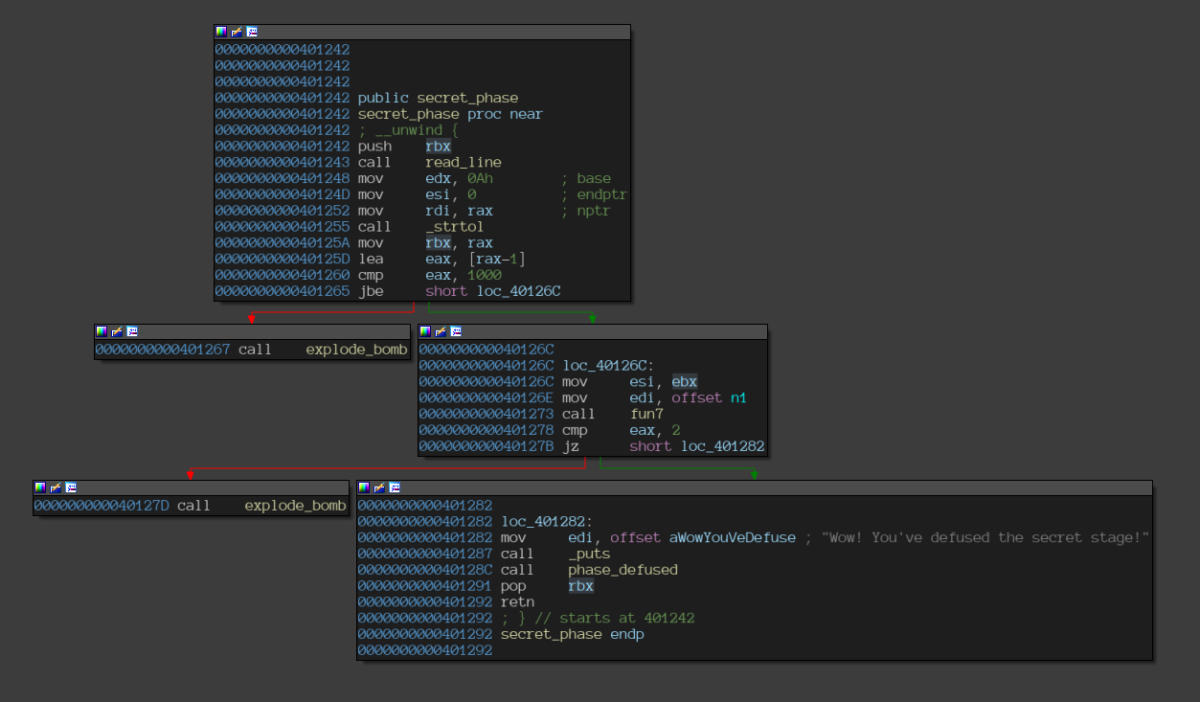

Checking out the fun7 function, it seems to be entangled in some sort of a recursive conditional parsing based on the user input.

Disassembly of the “fun7” function.

Disassembly of the “fun7” function.

We’ll leave it up to Angr to bypass the mess and just give us the answer.

Therefore,

- User input:

RAXregister - Comparison value: conditional parsing inside

fun7.

Since no other push to stack exists in the function, we can pop values like before, while keeping in mind to pop the value we setup the stack with first.

Read this page implemented in this IPython Notebook for a step-by-step explanation on the approache