5 minutes

Simple Code Injection Techniques for ELF

Bare-Metal Binary Modification

- Modify an existing binary is by directly editing the bytes of a binary file in hexadecimal format, using a program like hexedit.

- Use a disassembler to identify the code or data bytes to be changed and then use a hex editor to make the changes.

- Advantage: Simple and requires only basic tools. Any padding bytes, dead code (such as unused functions), or unused data, can be overwritten with something new.

- Disadvantage: Only allows in-place editing. Can change code or data bytes but not add anything new. Inserting a new byte causes all the bytes after it to shift to another address, which breaks references to the shifted bytes. It’s difficult (or even impossible) to correctly identify and fix all the broken references, because the relocation information needed for this is usually discarded after the linking phase.

- Works for cases like replacing malware’s anti-debugging checks with nop.

- Off-by-one bugs typically occur in loops when the programmer uses an erroneous loop condition that causes the loop to read or write one too few or one too many bytes.

Modifying Shared Library Behavior Using LD_PRELOAD

- LD_PRELOAD is an environment variable influencing the behavior of the dynamic linker. It allows you to specify one or more libraries for the linker to load before any other library, including standard system libraries such as libc.so. If a preloaded library contains a function with the same name as a function in a library loaded later, the first function is the one that will be used at runtime. This allows you to override library functions (even standard library functions like malloc or printf) with your own versions of those functions.

- The dlfcn.h header is often included when writing libraries for use with LD_PRELOAD because it provides the dlsym function.

Injecting a Code Section

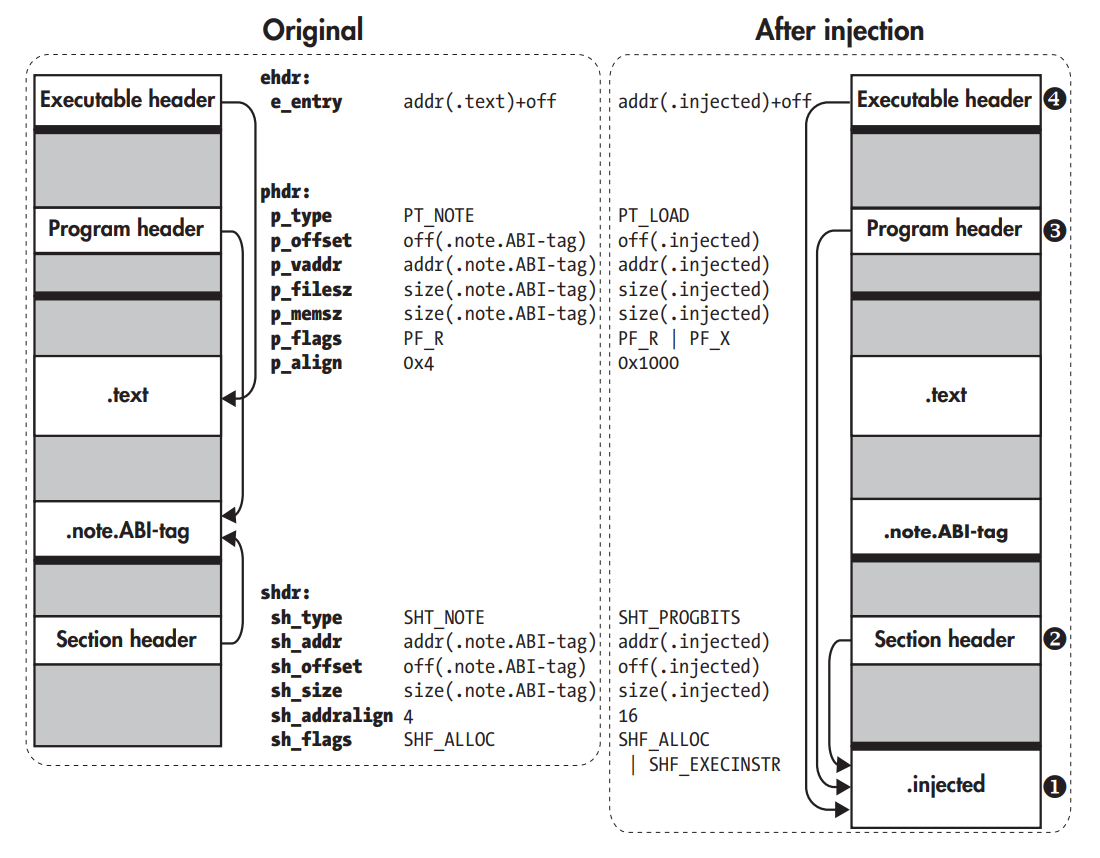

Replacing .note.ABI-tag with an injected code section.

Replacing .note.ABI-tag with an injected code section.

Step ➊ is to add a new section to an ELF binary, you first inject the bytes that the section will contain by appending them to the end of the binary. Next, you create a section header ➋ and a program header ➌ for the injected section. The program header table is usually located right after the executable header ➍, thus overwrite an existing program header instead of adding an extra one to prevent shifting of all the sections and headers that come after it.

- You can always safely overwrite is the PT_NOTE header, which describes the PT_NOTE segment. The PT_NOTE segment encompasses sections that contain auxiliary information about the binary. If this information is missing, the loader simply assumes it’s a native binary.

Step ➋ is overwriting one of the .note.* section headers to turn it into a header for the new code section (.injected). Choosing to overwrite the header for the .note.ABI-tag section, the sh_type is changed from SHT_NOTE to SHT_PROGBITS to denote that the header now describes a code section. Moreover, the sh_addr, sh_offset, and sh_size fields are changed to describe the location and size of the new .injected section instead of the now obsolete .note.ABI-tag section. Finally, the section alignment (sh_addralign) is changed to 16 bytes to ensure that the code will be properly aligned when loaded into memory, and the SHF_EXECINSTR flag is added to the sh_flags field to mark the section as executable.

Step ➌ is where the PT_NOTE program header is changed by setting p_type to PT_LOAD to indicate that the header now describes a loadable segment instead of a PT_NOTE segment. This causes the loader to load the segment (which encompasses the new .injected section) into memory when the program starts.

Step ➍ is redirecting the entry point (e_entry field in the ELF executable header), is made to point to an address in the new .injected section, instead of the original entry point, which is usually somewhere in .text. Done only if some code in the .injected section is to be run right at the start of the program.

Calling Injected Code

Injected code might be required to call at any instant during the execution of the binary. Following are the ways to call the injected code:

Entry Point Modification

Find entry point address via readelf and replace those bytes with the address of injected code via hex bytes editors or specific scripts.

Hijacking Constructors and Destructors

ELF binaries compiled with gcc contain sections called .init_array and .fini_array, which contain pointers to a series of constructors and destructors, respectively. By overwriting one of these pointers, the injected code can be invoked before or after the binary’s main function, depending on which one is overwritten.

Hijacking GOT Entries

Use objdump to view the .got.plt section to find out the address stored in the GOT entry used by the PLT stub. This address is replaced by the address of the injected code. Can also be done at runtime since the .got.plt section is writable.

Hijacking PLT Entries

Modify the PLT stub itself. Replace the indirect jmp instruction to a relative offset with a direct jmp instruction to the injected code inside the stub.

Redirecting Direct and Indirect Calls

Use a disassembler to locate the calls to modify and then overwrite them, using a hex editor to replace them with calls to the injected function instead of the original.

When redirecting an indirect call (as opposed to a direct one), the easiest way is to replace the indirect call with a direct one. However, this isn’t always possible since the encoding of the direct call may be longer than the encoding of the indirect call. In that case, you’ll first need to find the address of the indirectly called function that you want to replace, for instance, by using gdb to set a breakpoint on the indirect call instruction and inspecting the target address. Once you know the address of the function to replace, you can use objdump or a hex editor to search for the address in the binary’s .rodata section. If you’re lucky, this may reveal a function pointer containing the target address. You can then use a hex editor to overwrite this function pointer, setting it to the address of the injected code. If you’re unlucky, the function pointer may be computed in some way at runtime, requiring more complex hex editing to replace the computed target with the address of the injected function.

Citation: Practical Binary Analysis.