13 minutes

The ELF Format

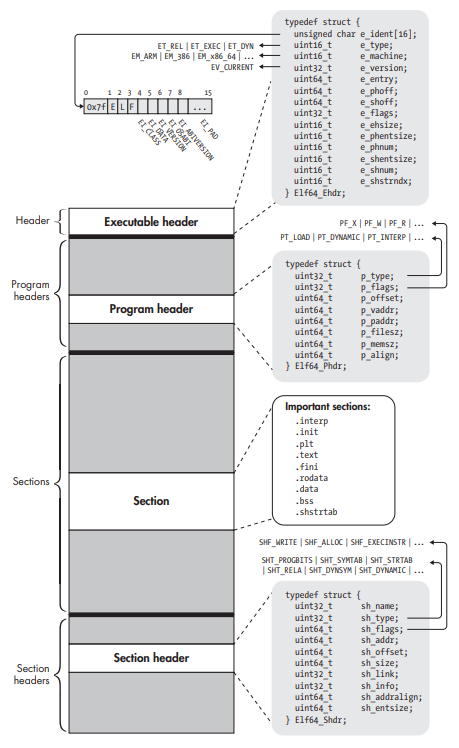

ELF binaries really consist of only four types of components:

- Executable Header

- Program Headers (optional)

- Sections

- Section Headers, one per section (optional)

64-bit ELF binary structure.

64-bit ELF binary structure.

Executable Header

- Every ELF file starts with an executable header, which is just a structured series of bytes telling you that it’s an ELF file and other metadata.

- Format of executable header: /usr/include/elf.h

typedef struct {

unsigned char e_ident[16]; /* Magic number and other info */

uint16_t e_type; /* Object file type */

uint16_t e_machine; /* Architecture */

uint32_t e_version; /* Object file version */

uint64_t e_entry; /* Entry point virtual address */

uint64_t e_phoff; /* Program header table file offset */

uint64_t e_shoff; /* Section header table file offset */

uint32_t e_flags; /* Processor-specific flags */

uint16_t e_ehsize; /* ELF header size in bytes */

uint16_t e_phentsize; /* Program header table entry size */

uint16_t e_phnum; /* Program header table entry count */

uint16_t e_shentsize; /* Section header table entry size */

uint16_t e_shnum; /* Section header table entry count */

uint16_t e_shstrndx; /* Section header string table index */

} Elf64_Ehdr;

Section Headers

- The code and data in an ELF binary are logically divided into contiguous non-overlapping chunks called Sections. Sections don’t have any predetermined structure; instead, the structure of each section varies depending on the contents.

- Some sections contain data that isn’t needed for execution at all, such as symbolic or relocation information.

- Every section is described by a Section Header, which denotes the properties of the section and allows you to locate the bytes belonging to the section.

- Exists to provide convenient organisation for use to linker. Only used at link time.

- The section headers for all sections in the binary are contained in the Section Header Table. It is optional since it is intended to provide a view for the linker only. If absent, e_shoff is set to zero.

- Format of a section header: /usr/include/elf.h

typedef struct {

uint32_t sh_name; /* Section name (string tbl index) */

uint32_t sh_type; /* Section type */

uint64_t sh_flags; /* Section flags */

uint64_t sh_addr; /* Section virtual addr at execution */

uint64_t sh_offset; /* Section file offset */

uint64_t sh_size; /* Section size in bytes */

uint32_t sh_link; /* Link to another section */

uint32_t sh_info; /* Additional section information */

uint64_t sh_addralign; /* Section alignment */

uint64_t sh_entsize; /* Entry size if section holds table */

} Elf64_Shdr;

Sections

- Following sections are present:

$ readelf --sections --wide a.out

There are 31 section headers, starting at offset 0x19e8:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0

[ 1] .interp PROGBITS 0000000000400238 000238 00001c 00 A 0 0 1

[ 2] .note.ABI-tag NOTE 0000000000400254 000254 000020 00 A 0 0 4

[ 3] .note.gnu.build-id NOTE 0000000000400274 000274 000024 00 A 0 0 4

[ 4] .gnu.hash GNU_HASH 0000000000400298 000298 00001c 00 A 5 0 8

[ 5] .dynsym DYNSYM 00000000004002b8 0002b8 000060 18 A 6 1 8

[ 6] .dynstr STRTAB 0000000000400318 000318 00003d 00 A 0 0 1

[ 7] .gnu.version VERSYM 0000000000400356 000356 000008 02 A 5 0 2

[ 8] .gnu.version_r VERNEED 0000000000400360 000360 000020 00 A 6 1 8

[ 9] .rela.dyn RELA 0000000000400380 000380 000018 18 A 5 0 8

[10] .rela.plt RELA 0000000000400398 000398 000030 18 AI 5 24 8

[11] .init PROGBITS 00000000004003c8 0003c8 00001a 00 AX 0 0 4

[12] .plt PROGBITS 00000000004003f0 0003f0 000030 10 AX 0 0 16

[13] .plt.got PROGBITS 0000000000400420 000420 000008 00 AX 0 0 8

[14] .text PROGBITS 0000000000400430 000430 000192 00 AX 0 0 16

[15] .fini PROGBITS 00000000004005c4 0005c4 000009 00 AX 0 0 4

[16] .rodata PROGBITS 00000000004005d0 0005d0 000011 00 A 0 0 4

[17] .eh_frame_hdr PROGBITS 00000000004005e4 0005e4 000034 00 A 0 0 4

[18] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000400618 000618 0000f4 00 A 0 0 8

[19] .init_array INIT_ARRAY 0000000000600e10 000e10 000008 00 WA 0 0 8

[20] .fini_array FINI_ARRAY 0000000000600e18 000e18 000008 00 WA 0 0 8

[21] .jcr PROGBITS 0000000000600e20 000e20 000008 00 WA 0 0 8

[22] .dynamic DYNAMIC 0000000000600e28 000e28 0001d0 10 WA 6 0 8

[23] .got PROGBITS 0000000000600ff8 000ff8 000008 08 WA 0 0 8

[24] .got.plt PROGBITS 0000000000601000 001000 000028 08 WA 0 0 8

[25] .data PROGBITS 0000000000601028 001028 000010 00 WA 0 0 8

[26] .bss NOBITS 0000000000601038 001038 000008 00 WA 0 0 1

[27] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 001038 000034 01 MS 0 0 1

[28] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 0018da 00010c 00 0 0 1

[29] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 001070 000648 18 30 47 8

[30] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 0016b8 000222 00 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), l (large)

I (info), L (link order), G (group), T (TLS), E (exclude), x (unknown)

O (extra OS processing required) o (OS specific), p (processor specific)

- The .init section (index 11) can be thought of as a constructor as it contains a single startup function that performs some crucial initialization needed to start the executable that the system executes before transferring control to the main function.

- The .fini section (index 15) is analogous to the .init section, except that it runs after the main program completes, essentially functioning as a kind of destructor.

- The .text section (index 14) is where the main code of the program resides. It contains a number of standard functions that perform initialization and finalization tasks, such as _start, register_tm_clones, and frame_dummy.

- The .init_array (index 19) section contains an array of pointers to functions to use as constructors. Each of these functions is called in turn when the binary is initialized, before main is called. The .init_array is a data section that can contain as many function pointers as you want, including pointers to your own custom constructors.

- The .fini_array (index 20) is analogous to .init_array, except that .fini_array contains pointers to destructors.

- In gcc, you can mark functions in your C source files as constructors by decorating them with __attribute__((constructor)).

- The pointers contained in .init_array and .fini_array are easy to change, making them convenient places to insert hooks that add initialization or finalization code to the binary to modify its behavior.

- The binaries produced by older gcc versions may contain sections called .ctors and .dtors instead of .init_array and .fini_array.

- The default values of initialized variables are stored in the .data (index 25) section, which is marked as writable since the values of variables may change at runtime.

- The .rodata (index 16) section, which stands for “read-only data,” is dedicated to storing constant values. Because it stores constant values, .rodata is not writable.

- The .bss (index 26) section reserves space for uninitialized variables. The name historically stands for block started by symbol, referring to the reserving of blocks of memory for (symbolic) variables. Unlike .rodata and .data, which have type SHT_PROGBITS, the .bss section has type SHT_NOBITS because .bss doesn’t occupy any bytes in the binary as it exists on disk, it’s simply a directive to allocate a properly sized block of memory for uninitialized variables when setting up an execution environment for the binary. Typically, variables that live in .bss are zero initialized, and the section is marked as writable.

- The .symtab (index 29) section contains a symbol table, which is a table of Elf64_Sym structures, each of which associates a symbolic name with a piece of code or data elsewhere in the binary, such as a function or variable.

- The actual strings containing the symbolic names are located in the .strtab (index 30) section. These strings are pointed to by the Elf64_Sym structures.

- In the stripped binaries the .symtab and .strtab tables are removed.

- The .dynsym (index 5) and .dynstr (index 6) sections are analogous to .symtab and .strtab, except that they contain symbols and strings needed for dynamic linking rather than static linking. Because the information in these sections is needed during dynamic linking, they cannot be stripped.

- The static symbol table has section type SHT_SYMTAB, while the dynamic symbol table has type SHT_DYNSYM. This makes it easy for tools like strip to recognize which symbol tables can be safely removed when stripping a binary and which cannot.

- .rel.* and .rela.* sections are of type SHT_RELA, meaning that they contain information used by the linker to perform relocations with each entry detailing a particular address where a relocation needs to be applied, as well as instructions on how to resolve the particular value that needs to be plugged in at this address. What all relocation types have in common is that they specify an offset at which to apply the relocation. There are two most common types of dynamic linking:

- GLOB_DAT(Global data) : This relocation has its offset in .got section. This type of relocation is used to compute the address of a data symbol and plug it into the correct offset in .got.

- JUMP_SLO(Jump Slots) : This relocation has its offset in the .got.plt section and represent slots where the addresses of library functions can be plugged in.

- The .dynamic (index 22) section functions as a “road map” for the operating system and dynamic linker when loading and setting up an ELF binary for execution. The .dynamic section contains a table of Elf64_Dyn structures, also referred to as tags. There are different types of tags, each of which comes with an associated value. Tags of type DT_NEEDED inform the dynamic linker about dependencies of the executable. The DT_VERNEED and DT_VERNEEDNUM tags specify the starting address and number of entries of the version dependency table, which indicates the expected version of the various dependencies of the executable. In addition to listing dependencies, the .dynamic section also contains pointers to other important information required by the dynamic linker (for instance, the dynamic string table, dynamic symbol table, .got.plt section, and dynamic relocation section pointed to by tags of type DT_STRTAB, DT_SYMTAB, DT_PLTGOT, and DT_RELA, respectively).

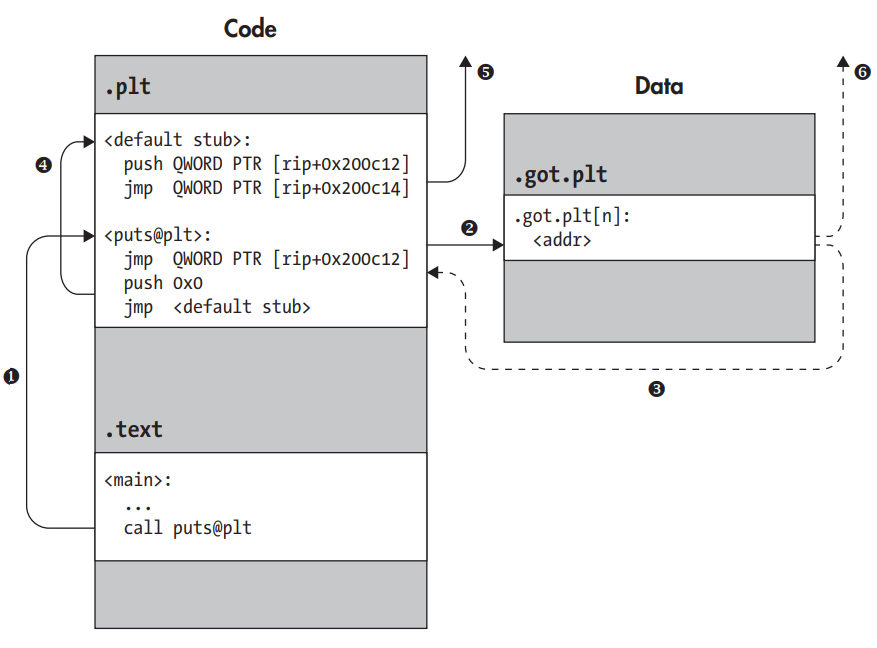

Lazy Binding

Many of the relocations are typically not done right away when the binary is loaded but are deferred until the first reference to the unresolved location is actually made. This is known as Lazy Binding. It ensures that the dynamic linker never needlessly wastes time on relocations; it only performs those relocations that are truly needed at runtime.

Lazy Binding.

Lazy Binding.

- Linker can be forced to perform all relocations right away by exporting an environment variable called LD_BIND_NOW, done when the application calls for real-time performance guarantees.

Lazy binding in Linux ELF binaries is implemented with:

- Global Offset Table (.got section).

- Data section.

- ELF binaries often contain a separate GOT section called .got.plt for use in conjunction with .plt in the lazy binding process. Relocations are of type R_386_JUMP_SLOT, which implies that they are branch relocations.

- The .got section is for relocations regarding global variables, all of type R_386_GLOB_DAT.

- Procedure Linkage Table (.plt section)

-

Code section that contains executable code.

-

The .plt section contain the actual stubs to lookup the addresses in .got.plt section.

-

The .plt.got is an alternative PLT that uses read-only .got entries instead of .got.plt entries. It’s used if you enable the ld option -z now at compile time, telling ld that you want to use now binding. This has the same effect as LD_BIND_NOW=1, but by informing ld at compile time, you allow it to place GOT entries in .got for enhanced security and use 8-byte .plt.got entries instead of larger 16-byte .plt entries.

-

Calling a shared library function via the PLT (referred by step num)

-

$ objdump -M intel --section .plt -d a.out

a.out: file format elf64-x86-64

Disassembly of section .plt:

➊ 00000000004003f0 <puts@plt-0x10>:

4003f0: push QWORD PTR [rip+0x200c12]

# 601008 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x8>

4003f6: jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x200c14]

# 601010 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x10>

4003fc: nop DWORD PTR [rax+0x0]

➋ 0000000000400400 <puts@plt>:

400400: jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x200c12]

# 601018 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x18>

400406: push ➌0x0

40040b: jmp 4003f0 <_init+0x28>

➍ 0000000000400410 <__libc_start_main@plt>:

400410: jmp QWORD PTR [rip+0x200c0a]

# 601020 <_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_+0x20>

400416: push ➎0x1

40041b: jmp 4003f0 <_init+0x28>

- First call to a library function (say puts) sends it to it’s plt entry (➋puts@plt). There it experiences a jump (step ➋) to an address which initially is the address of the next instruction (➌), thus jumping back (step ➌). The push instruction pushes an integer onto the stack which serves as an index/identifier for the current function stub. It then encounters another jump (step ➍) which sends it to the default stub (➊), which pushes another identifier (taken from GOT) and jumps, indirectly through GOT, to the dynamic linker (step ➎). Using the identifiers pushed by the PLT stubs, the dynamic linker figures out that it should resolve the address of puts and should do so on behalf of the main executable loaded into the process. This last bit is important because there may be multiple libraries loaded in the same process as well, each with their own PLT and GOT. The dynamic linker then looks up the address at which the puts function is located and plugs the address of that function into the GOT entry associated with puts@plt. The GOT entry now no longer points back into the PLT stub, as it did initially, but now points to the actual address of puts. At this point, the lazy binding process is complete. Finally, the dynamic linker satisfies the original intention of calling puts by transferring control to it. For any subsequent calls to puts@plt, the GOT entry already contains the appropriate (patched) address of puts so that the jump at the start of the PLT stub goes directly to puts without involving the dynamic linker (step ➏).

- zGOT has been incorporated because:

- GOT is a data section and thus it’s okay for it to be writable. Therefore it makes sense to have the additional layer of indirection through the GOT since this extra layer of indirection allows you to avoid creating writable code sections (leaving PLT read-only). While an attacker may still succeed in changing the addresses in the GOT, this attack model is a lot less powerful than the ability to inject arbitrary code.

- A dynamic library will have only exist in a single physical copy while it will likely be mapped to multiple completely different virtual address for each process. Thus you can’t patch addresses resolved on behalf of a library directly into the code because the address would work only in the context of one process and break the others. Patching them into the GOT instead does work because each process has its own private copy of the GOT.

Program Headers

- The Program Header Table provides a Segment view of the binary, as opposed to the section view provided by the Section Header Table.

- Format of a program header: /usr/include/elf.h

typedef struct {

uint32_t p_type; /* Segment type */

uint32_t p_flags; /* Segment flags */

uint64_t p_offset; /* Segment file offset */

uint64_t p_vaddr; /* Segment virtual address */

uint64_t p_paddr; /* Segment physical address */

uint64_t p_filesz; /* Segment size in file */

uint64_t p_memsz; /* Segment size in memory */

uint64_t p_align; /* Segment alignment */

} Elf64_Phdr;

$ readelf --wide --segments a.out

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x400430

There are 9 program headers, starting at offset 64

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000040 0x0000000000400040 0x0000000000400040 0x0001f8 0x0001f8 R E 0x8

INTERP 0x000238 0x0000000000400238 0x0000000000400238 0x00001c 0x00001c R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x0000000000400000 0x0000000000400000 0x00070c 0x00070c R E 0x200000

LOAD 0x000e10 0x0000000000600e10 0x0000000000600e10 0x000228 0x000230 RW 0x200000

DYNAMIC 0x000e28 0x0000000000600e28 0x0000000000600e28 0x0001d0 0x0001d0 RW 0x8

NOTE 0x000254 0x0000000000400254 0x0000000000400254 0x000044 0x000044 R 0x4

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x0005e4 0x00000000004005e4 0x00000000004005e4 0x000034 0x000034 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000 0x000000 0x000000 RW 0x10

GNU_RELRO 0x000e10 0x0000000000600e10 0x0000000000600e10 0x0001f0 0x0001f0 R 0x1

➊ Section to Segment mapping:

Segment Sections...

00

01 .interp

02 .interp .note.ABI-tag .note.gnu.build-id .gnu.hash .dynsym .dynstr .gnu.version .gnu.version_r .rela.dyn

.rela.plt .init .plt .plt.got .text .fini .rodata .eh_frame_hdr .eh_frame

03 .init_array .fini_array .jcr .dynamic .got .got.plt .data .bss

04 .dynamic

05 .note.ABI-tag .note.gnu.build-id

06 .eh_frame_hdr

07

08 .init_array .fini_array .jcr .dynamic .got

- An ELF segment encompasses zero or more sections, essentially bundling these into a single chunk (➊). Since segments provide an execution view, they are needed only for executable ELF files and not for non-executable files such as relocatable objects.

Citation: Practical Binary Analysis.